2020 is shaping up to be a really exciting year for Gatsby, with lots of ambitious projects on the roadmap. On the Gatsby Cloud team, we’ve been getting all of our ducks in a row, making sure we’re all set to hit the ground running. One of the areas we’ve been focusing on is our GitHub workflow.

We were seeing a lot of “stalled” Pull Requests (PRs) - work was being put up for review, but not receiving prompt attention. These PRs tended to be quite large and complex, essentially containing the entirety of work for a given feature or refactor.

Monolithic PRs are difficult to review. In addition to the time investment, they also tend to require a lot of mental energy; to be an effective reviewer, you need to build up a mental picture of the change, and the larger that change is, the more context needs to be held in focus. Additionally, large PRs tend to develop their own inertia. If a reviewer has a great idea for an alternative approach, but it would require scrapping most of the work already done in the PR, it’s not likely to be acted upon (if it’s even shared in the first place).

It’s easy to say that developers should limit the size of their PRs, but this is very much easier said than done. GitHub really doesn’t make it clear or intuitive how to break work up into multiple reviewable units. PRs are based on branches, and it’s not always clear how to juggle multiple branches. Even for folks who are comfortable with Git, the path can be very tricky.

Ideally, the developer could spin up new PRs as they went, allowing them to solicit feedback early, without being blocked while waiting for it. If the feedback does require significant changes, it should be easy to integrate those changes into their more-recent work.

This blog post explains how we solved for these concerns!

Workflow overview

Let’s say we’re working on a blog, and want to incorporate a headless CMS, switching from using local markdown files and hardcoded data.

First, we create a new branch, feat/headless-cms. This will be our root branch; we’ll merge PRs as we go into this branch. We never commit to it directly, and so for the time being, it’s a clone of our deploy branch (typically master or staging, whichever branch features are typically merged into). Even though it doesn’t hold any commits yet, we should push it to GitHub.

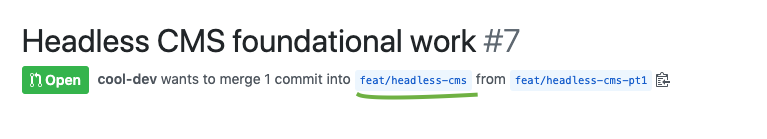

Right after creating that branch and pushing it to GitHub, we create another branch, feat/headless-cms-pt1. This will be an incremental branch, holding some of the changes needed for this feature. We get to work on the most fundamental parts of this change (for example, adding a source plugin and configuring it to pull data from our new CMS). Once we have a “hello world” based on this new architecture, we’re ready to solicit some feedback. We push our branch to GitHub, and open a PR comparing our incremental branch to our root branch:

In a traditional workflow, opening a PR makes it hard for us to keep working on that feature; we’ll bloat the PR if we keep committing to it, and it’s not obvious how to manage “chained” PRs. This is a big part of why teams wind up with big PRs.

In this alternative workflow, we can keep working. We’ll create a new incremental branch, feat/headless-cms-pt2, forked from feat/headless-cms-pt1.

Here’s a visualization of this setup:

Our first incremental branch has two commits, A and B. Our second branch is forked from that first branch, and adds a new commit C.

When changes are requested

At first blush, this workflow might seem problematic to you. How can you start work on the second part of the feature before getting feedback on the first? What if a bunch of changes are requested?

In fact, this workflow shines when it comes to implementing requested changes.

Let’s say that we get feedback that fundamentally changes how we want to approach it. It requires a good amount of restructuring. We do those changes, and create a new commit, D, on our pt1 branch:

Our pt1 PR is approved (🎉), but now we have to reconcile our pt2 branch. Given that it built on a now-outdated structure, there’s a good chance we’ll have some conflicts.

We check out the pt2 branch and rebase it onto the updated pt1 branch:

If you’re not familiar with rebasing, it’s an alternative to merging that involves “replaying” commits over a different branch. This can be a weird idea for folks who are used to merging, and it takes most people a bit of practice to get comfortable with it. You can learn more about rebasing in this article from Algolia.

Conflicts

After running that rebase command, we’ll likely get a conflict, since our commit C is incompatible with the changes in D. Here’s the cool thing, though: the conflicts show us exactly what needs to change.

For many, Git conflicts are a stressful experience, one to be avoided at all costs. In this case, though, conflicts are actually pretty helpful, because they give you targeted information about the problem.

Imagine if we had instead opened one big PR with all of our changes. We’d get the same feedback: fundamental restructuring requested. Now it’s on us, the developer, to figure out which parts of this big PR need to change, and which parts can stay the same. We need to do the work of hunting down the conflicts.

In this alternative flow, we’re leveraging Git to show us what work needs to be done.

Once we’ve fixed all the conflicts, we can finish up our rebase by running the following:

After rebasing, our Git branches look like this:

You’ll notice that our C commit—the only commit in our pt2 branch—has been replaced with E. This is because it’s no longer the same commit; it includes the changes that we dealt with in our rebase.

Because we’ve rewritten the history, by turning C into E, we need to force-push to update our PR on GitHub:

Merging PRs

When PRs are approved, we can merge them. We have a couple options in this flow:

- Merge from the last one down (merge

pt2intopt1, and thenpt1into the root branch) - Merge from the first one up (merge

pt1into the root branch, and then mergept2into the root branch)

In general, the second strategy is better, because it’s more flexible; you don’t need to wait for all work to be done before you can start merging!

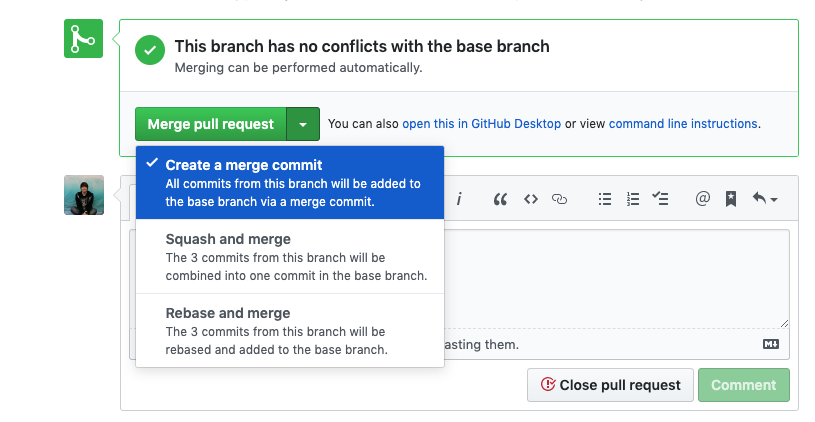

We’ll start by merging pt1 into the root branch. Merge it in using the standard “Create a merge commit” option:

Next, we need to update our pt2 branch. Right now it’s still being compared to pt1, a branch which has since been merged. We want to point it to our root branch, feat/headless-cms, instead.

We can do this on GitHub by changing the base. GitHub has great docs that cover this. In effect, it allows us to switch which branch we want to merge our changes into.

With our new base set, our tree looks like this:

A new commit M was added, representing the merge.

🙅♀️ No squashing 🙅♀️

It’s important that we stick with the default “Create a merge commit” option, in the short term. Before merging our changes into master, we’ll be able to squash everything into 1 commit, but for now, preserving the history is important, in order for Git to correctly track what’s happening.

When branches are visualized, they’re often depicted as groups of commits. This very blog post is guilty of this as well: in the above diagram, our root branch is shown as “containing” commits A, B, and D.

In fact, branches are much thinner abstractions than that; all they do is point towards a specific commit. This works because commits themselves are similar to a linked list; every commit also points to its parent commit.

A more accurate representation of our current state would look like this:

Every commit points to its parent, and branches are just references to a particular commit.

Let’s say we had squash-merged our pt1 branch into the root branch. We would wind up with two parallel universes. In our root branch, we’d have a brand new commit S, representing the squashed contents of pt1. Our pt2 branch, meanwhile, doesn’t know about any of this; the chain of commits still includes the “unsquashed” pt1 work.

These universes collide when we try to change the base, to point pt2 at the root branch:

The Git history pollution isn’t a huge deal, since we’ll have the chance to squash or clean this up before deploying, but it can lead to weird issues and nonsensical conflicts.

If you do wind up squash-merging a branch, you’ll need to manually snip out the duplicate commits. You can do this with an interactive rebase:

Incorporating external changes

The work we’re doing in this example to migrate to a headless CMS might take a week or two. In that time, other folks at the org will undoubtedly be shipping a bunch of other stuff. We may wish to update our feature to incorporate those changes!

To accomplish this, we’ll do some more local rebasing:

Essentially, we’re scooting all of our changes to happen after the most recent commit on master. It’s important to rebase instead of merge so that we don’t “interleave” the changes from other branches—we’re keeping all of our work tightly clustered for now. This can be a bit tedious if you have lots of incremental branches, so you may wish to hold off on this until you’ve merged everything into the root branch.

And on and on

The neat thing about this flow is that it isn’t limited to two incremental branches; we can keep going!

In this example, we could check out a new branch, pt3, based off of pt2. And then a fourth, pt4, from pt3:

No matter how many branches we have, the process is always the same when we’re ready to start merging:

- Merge the earliest open PR into the root branch, using the standard “merge” option.

- Change the base of the next branch to point at the root branch

Ship it

What about when all the work is done, and we’re ready to release?

At this point, we’ll have a string of commits on our root branch, feat/headless-cms. We can open a PR against our deploy branch (eg. master or staging). Because all the work has already been reviewed, we don’t need to go through another review cycle.

At this point, we have the freedom to organize our commits however we want. We can squash it all into 1 commit, or combine them into logical chunks. It’s up to us to decide how we want our work to be reflected in the history.

Drawbacks

No flow is without tradeoffs, and this one has a couple:

1. It rewrites history

This flow relies heavily on rebasing, which rewrites history. This means that pushing to GitHub requires a force-push, which can be scary, especially for folks newer to using Git.

This also makes it harder to collaborate on a feature; you need to communicate clearly before rebasing, to make sure everyone’s work is in beforehand.

2. It involves some branch juggling

With 3-4 incremental branches, developers have to bounce between them and make sure they’re kept in sync. This can be tedious.

When should I use this flow?

Given the drawbacks mentioned above, this is probably not something that should be adopted for every change. It provides the most benefit for changes that are too big to fit into a single PR.

It’s hard to define a “big” PR - sometimes, a PR changes 2,000 lines of code, but only because a codemod slightly tweaked a bunch of files. Other times, a 300-line PR is so dense that it could benefit from being broken up into smaller pieces.

The amount of time it takes to review a PR is often correlated with the amount of time it took to write it, so maybe a better rule of thumb is that a PR is too big if it encompasses more than a few days’ worth of development effort.

It’s also worth mentioning that feature flags are a viable alternative to this flow. Feature flags are toggles that can be flipped, and read from within the codebase. This means that unfinished work can be merged into production as long as it’s hidden behind a feature flag. Once all the changes have been merged, the flag can be flipped, and the feature will be enabled.

Feature flags are great because they allow developers to break monolithic changes into smaller PRs, but sometimes the cost of architecting a change to fit behind a feature flag is more trouble than it’s worth (eg. sprawling changes that affect many different parts of the codebase, or large refactors).

When using feature flags, a streamlined version of this flow can still be useful, to ensure that developers aren’t blocked while waiting for feedback.

Conclusion

We’ve been using this flow on the Cloud team for a few weeks now, and it’s been a pretty big boon to our productivity! PRs are tailored to be easy to review, and developers don’t have to switch tasks to avoid being blocked while awaiting feedback. It’s pretty great.

Parts of this flow can be tedious, as the same commands need to be repeated over and over again to update multiple incremental branches. It might be interesting to explore some additional tooling, to manage this for us! But in the meantime, it’s a small price to pay.

If you give this flow a shot, I’d love to hear how it works for you! Feel free to reach out on Twitter.